Growth of Monolayer MoS2 on Hydrophobic Substrates to Prevent Ambient Degradation

I have co-developed a novel method to prevent the ambient degradation of monolayer (ML) molybdenum disulfide (MoS2). ML MoS2 is a 2-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenide (TMD) with unique properties like atomic-scale thinness, mechanical flexibility, direct band gap, and strong spin orbit coupling.1 ML MoS2 has a wide variety of applications in optoelectronics, spintronics, and sensors.1 However, ML MoS2 is limited in its practical application due to its propensity to degrade under exposure to ambient air.2 Previous studies have reported methods to prevent degradation such as encapsulation or vacuum storage,3 but these methods are inefficient and not scalable. Thus, my feasible degradation prevention method is of great interest to the scientific community and may pave the path to the widespread implementation of ML MoS2 in technology.

It has been previously reported that degradation of ML MoS2 proceeds by the formation of dendrites with a fractal dimension close to that of diffusion limited aggregation, indicating that the diffusion of water molecules on the MoS2 ML is likely involved in the degradation mechanism.4 The water molecules may be getting onto the ML MoS2 mainly from the substrate or the ambient air. Thus, it is of interest to investigate the effects of substrate hydrophobicity on the degradation.

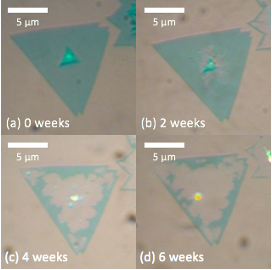

Figure 1: Optical images of MoS2 grown on SiO2 in 100% RH environment

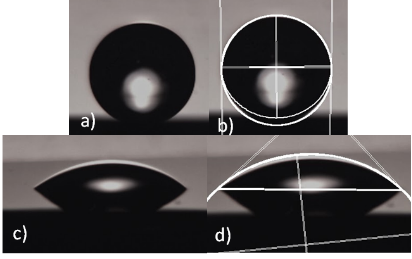

Figure 2: Contact angles of (b) Si3N4 substrate and (d) SiO2 substrate

After studying ML MoS2 in a 100% RH environment, I found that the degradation was greatly accelerated. The samples began degrading in less than 2 weeks and were almost completely destroyed by the 6th week in the humid environment (Fig. 1). In the control group, ML MoS2 in standard laboratory conditions (40% RH) took about 1 year to show noticeable degradation. I verified the degradation with atomic force microscopy (AFM) and Raman spectroscopy. I concluded that the high concentration of water vapor accelerated the degradation due to the liquefaction of oxides that leaves a layer unprotected and susceptible to degradation.5 I also concluded that since the degradation rate increased with increasing RH, then the amount of water molecules adsorbed on the SiO2 substrate likely was a limiting factor in the degradation. Therefore, I hypothesized that decreasing the amount of water adsorbed on the substrate would decrease the degradation rate. To test this hypothesis, I explored how hydrophobic and hydrophilic substrates affect the degradation rate of MoS2. But first, I needed to investigate the hydrophobicity of various substrates.

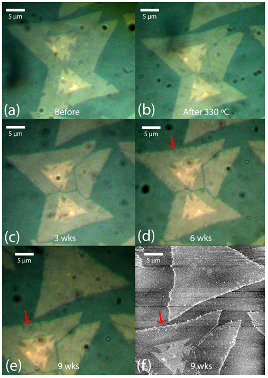

Figure 3: ML MoS2 on Si3N4 after weeks in ambient conditions

I independently designed and built my own apparatus to measure the contact angle of 5 μL water droplets on substrates. After taking images of the droplets I used the Image J Software6 to approximate the droplet profile with an ellipse (Fig. 2). I then differentiated the ellipse and calculated the contact angle. I found that the water contact angles of our SiO2 substrates were 44.73° ± 0.50° and the measured water contact angle of Si3N4 was 89.63° ± 0.40°. Although literature values for SiO2 and Si3N4 substrates exist, hydrophobicity is dependent on substrate thickness, so it was important that I measured it. From the contact angle measurements, I concluded that SiO2 is hydrophilic and that Si3N4 is hydrophobic.

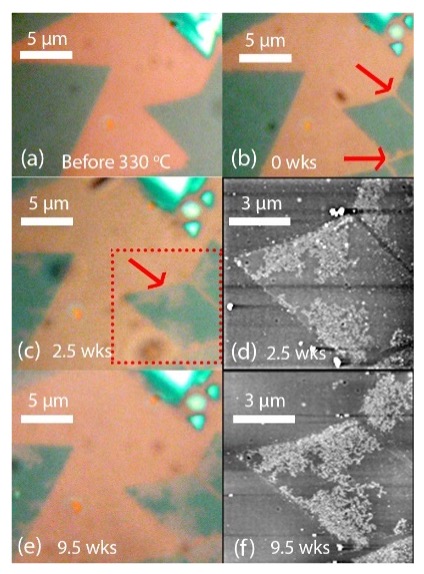

Figure 4: ML MoS2 on SiO2 after weeks in ambient conditions

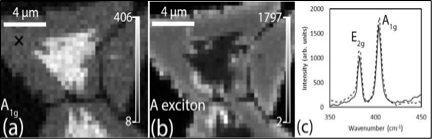

Next, I studied the effect of substrate hydrophobicity on the degradation of ML MoS2. Over several weeks, I observed the degradation of MoS2 grown on SiO2 and Si3N4 substrates. I used a method known to accelerate the degradation of ML MoS2, so that I could study the degradation process in a time frame of weeks rather than a year. This method consists of first heating the samples in air prior to leaving the samples in ambient conditions at RT.4 I found that MoS2 grown on Si3N4 substrates barely degraded (Fig. 3), while MoS2 grown on SiO2 substrates significantly degraded (Fig. 4). I analyzed the data collected from AFM and found elevated dendrite structures, which has been reported to be a clear sign of degradation.4 Additionally, I verified the degradation by comparing the Raman peaks and photoluminescence intensities of the MoS2 on Si3N4 just after growth (0 weeks) and at the 9-week mark. The intensities were remarkably uniform, indicating that little to no degradation occurred (Fig. 5). This finding will help device manufacturers make the smart decision of incorporating hydrophobic substrates in the microenvironments of their devices to lengthen the lifespan of MoS2-based devices.

Figure 5: ML MoS2 on Si3N4 intensity maps of (a) A1g & (b) A exciton peaks at 9-week mark. (c) shows Raman spectra of the sample immediately after growth (dotted line) and at 9-week mark (solid line)

In conclusion, I found that at ambient 40% RH conditions, the degradation rate of CVD-grown ML MoS2 is limited by the amount of water on the ML. I found that CVD-grown ML MoS2 films grown on Si3N4, a hydrophobic substrate, degrade significantly less than films grown on SiO2, a hydrophilic substrate, when pre-heated and then exposed to ambient air (40% RH) and room temperature. I propose that this reduced degradation rate occurs because of the reduced number of water molecules diffusing from the substrate onto the ML. These results demonstrate that 2D TMDs grown on hydrophobic substrates may be more resilient to degradation from ambient environments in cases in which the amount of water adsorbed on the ML is a limiting factor in the degradation rate. Future work will explore how superhydrophobic substrates influence degradation. If the correlation between hydrophobicity and degradation rate continues, then a superhydrophobic substrate may further slow the degradation rate, or even completely halt degradation. My individual contributions to these projects resulted in a co-authorship of a publication in the journal MRS Advances.7

-

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis, A., … & Strano, M. S. (2012). Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nature nanotechnology, 7(11), 699-712. ↩︎ ↩︎2

-

Gao, J., Li, B., Tan, J., … & Koratkar, N. (2016). Aging of transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. ACS nano, 10(2), 2628-2635. ↩︎

-

Lee, G. H., Cui, X., Kim, Y. D., … & Hone, J. (2015). Highly stable, dual-gated MoS2 transistors encapsulated by hexagonal boron nitride with gate-controllable contact, resistance, and threshold voltage. ACS nano, 9(7), 7019-7026. ↩︎

-

Yao, K., Femi-Oyetoro, J. D., Yao, S., … & Perez, J. M. (2019). Rapid ambient degradation of monolayer MoS2 after heating in air. 2D Materials, 7(1), 015024. ↩︎ ↩︎2 ↩︎3

-

Afanasiev, P., Lorentz, C. (2019). Oxidation of nanodispersed MoS2 in ambient air: the products and the mechanistic steps. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 123(12), 7486-7494. ↩︎

-

Rasband, W. S. (2011). National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. http://imagej. nih. gov/ij/. ↩︎

-

Yao, K., Banerjee, D., Femi-Oyetoro, J. D., … & Perez, J. (2020). Growth of Monolayer MoS2 on Hydrophobic Substrates as a Novel and Feasible Method to Prevent the Ambient Degradation of Monolayer MoS2. MRS Advances, 1-9. ↩︎