The Bertrand Paradox Is Hardly a Paradox

Principle of Indifference

Suppose I tell you I have a six-sided die in my pocket, out of your line of sight, and I ask you, “If I roll the dice, what is your credence that it lands on one?” You don’t know anything about the dice besides the fact that it has six-sides, which means that there are six possible outcomes. Since you don’t have any other information about the dice, it seems most reasonable to distribute your credences equally amongst the six possible outcomes. Thus, you claim that your credence in the die landing on 1 is \(\frac{1}{6}\). In this situation, you have invoked the principle of indifference. The principle of indifference states a rational agent should hold equal credence amongst all possible outcomes in the absence of relevant evidence. In other words, if there is no reason to think that one outcome is more likely than another outcome, then one should assign equal credence to each possible outcome. In this situation, there is no reason to believe that the dice is rigged in some way. Although the principle of indifference usually produces reasonable credences, there are certain sets of propositions that produce ill-defined credences. In 1889, Joseph Bertrand posed a problem that showed the inconsistency of the principle of indifference.

Bertrand Paradox

The Bertrand paradox is the following:

Consider a circle in which an equilateral triangle has been inscribed. Suppose a chord of the circle is chosen at random. What is the probability that the length of the chord is greater than the length of a side of the inscribed triangle?”

Bertrand offered three approaches to solving this problem, each of which results in a different, contradictory answer!

Approach 1: Random Endpoints Method

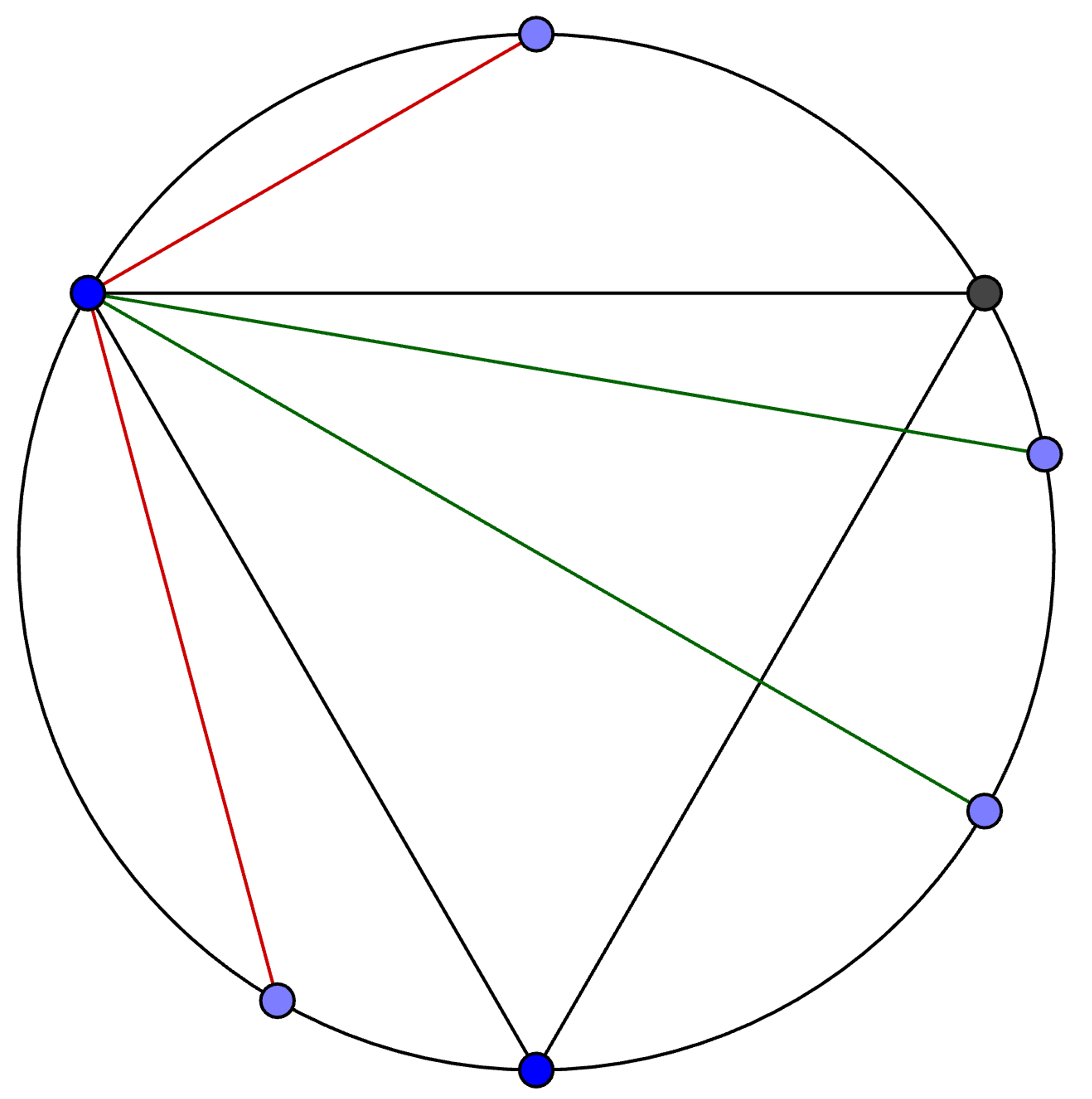

Figure 1: Construction of random endpoints method

Randomly select two points on the circumference of the circle. These points will be the endpoints of the chord. Draw an equilateral triangle inscribed in the circle with one of its vertices being one of the endpoints of the chord. If the other endpoint of the chord is situated between the other two vertices of the triangle, then the chord is longer than the side of the triangle. Since the equilateral triangle divides the circumference of the circle into three arcs of equal length, each arc has length \(\frac{2 \pi R}{3}\), where \(R\) is the radius of the circle. Thus, we calculate that the probability that the length of the chord is greater than the side of the triangle is \(\frac{1}{3}\).

Approach 2: Random Radius Method

Figure 2: Construction of random radius method

The second approach is the random radius method. Draw a radius of the circle. Draw an equilateral triangle inscribed in the circle such that one of its sides is perpendicular to the radius. Randomly select a point on the radius to be the midpoint of a chord. If the midpoint is selected to be within the triangle, then the length of the chord will be longer than the side of the triangle. Using trigonometry, we calculate that the length of the segment of the radius enclosed within the triangle is \(\frac{R}{2}\), where \(R\) is the radius of the circle. Thus, the probability that the length of the chord is greater than the side of the triangle is \(\frac{1}{2}\).

Approach 3: Random Midpoint Method

Figure 3: Construction of random midpoint method

The third approach is the random midpoint method. Draw a concentric circle within the inscribed equilateral triangle. Randomly select a point anywhere within the larger circle. This point will be the midpoint of the chord. If this point lies within the concentric circle, then the length of the chord will be longer than the side of the triangle. Using trigonometry, we find that the radius of the concentric circle is \(\frac{R}{2}\), where \(R\) is the radius of the larger circle. We calculate the probability of the point lying within the concentric circle to be \(\frac{\frac{\pi R^2}{4}}{\pi R^2}= \frac{1}{4}\). Thus, the probability that the length of the chord is greater than the side of the triangle is \(\frac{1}{4}\).

So What’s Wrong?

Each approach is mathematically valid, yet each approach yields different answers for seemingly the same problem! This is a particularly problematic result because it seems like we don’t have a consistent method of defining an uninformative prior. The paradox lies in the invocation of the principle of indifference. We use the principle of indifference in how we “randomly” select the chord. However, this is an inappropriate use of the principle of indifference since we are not using the same method of randomly selecting the chord. When we use different methods of randomly selecting the chord, we are essentially creating distinct problems. Thus, the Bertrand paradox does not have a unique solution. Since there are several approaches to solving the problem and since there is no reason to prefer one approach over another, there is no well-defined solution to Bertrand’s paradox as it is currently stated. However, Bertrand’s paradox will have a unique solution if the method of randomly selecting chords is specified.

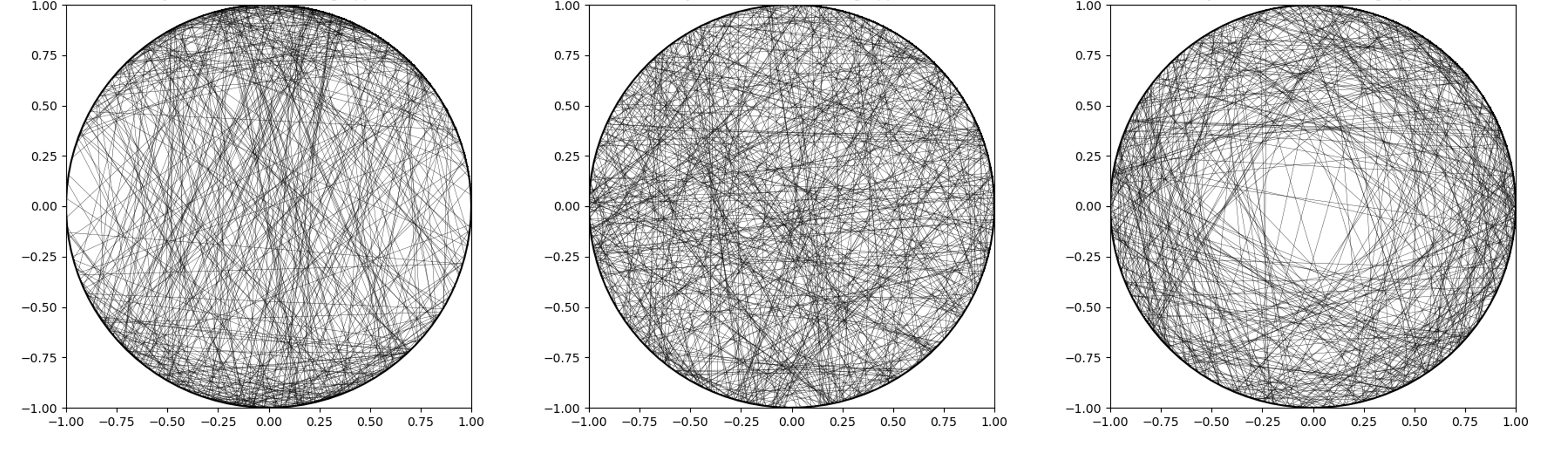

Figures 4, 5, and 6 (left to right): randomly generated chords using random endpoints, radius, and midpoint methods, respectively

To better illustrate how each approach creates a distinct problem, I wrote a Python script that generates chords according to the method outlined in each of the three approaches.

By inspection, one can notice that the approaches differ slightly in their distributions of chords. For example, the density of chords near the center of the circle in Figure 6 is significantly lower than in Figure 4 and 5. It now becomes clear that each approach is solving a different problem because the distribution of chords is clearly different between approaches. The reason Bertrand’s paradox appears paradoxical at first is that we assume contradictory probability distributions for our chords. For example, in approach 1, we claim that we are selecting endpoints uniformly distributed along the circumference of the circle, but this method of selecting chords implies a non-uniform distribution for the other two methods of randomly selecting chords. It’s almost as if we are measuring the width of a poster and getting the three results 36 inches, 3 feet, and 1 yard, and exclaiming, “why the hell am I getting 3 different results for the same object?! How can the answer be 36, 3, and 1 at the same time?!” The confusion lies in the fact that we are comparing measurements in different units. If we want to make reasonable comparisons between the three approaches to solving Bertrand’s paradox, we need to convert the “units of approach #1” into the units of the other approaches (a form of normalization, if you will).

Conclusion

Thus, we have shown that the Bertrand paradox does not jeopardize the principle of indifference. Instead, it shows us that we need to be especially careful while formulating probability problems, especially problems where the relevant variables are continuous. If the problem is not well-defined, then we can devise multiple solutions to the problem that result in different, contradictory answers!

If you’re interested in learning about other Bertrand-like paradoxes, try solving the wine/water paradox:

A mixture is known to contain a mix of wine and water in proportions such that the amount of wine divided by the amount of water is a ratio \(x\) lying in the interval \(\frac{1}{3} \leq x \leq 3\) (i.e. 25-75% wine). We seek the probability, \(P^{\ast }\) say, that \(x \leq 2\) (i.e. less than or equal to 66%.)