Rationalizing Punishment

U.S. inmates are subjected to cruel forms of punishment. Most people defend the punishment of prisoners as a necessary evil to deter others from committing crimes and also to hold the prisoner responsible for their crimes. However, the punishment of prisoners is an unnecessary evil. Punishing prisoners does not serve as an effective method of crime deterrence. Furthermore, the U.S. prison system’s forms of punishment deny prisoners their human rights. Thus, we must advocate for humane prisons and the rights of prisoners. Building a prison system that focuses on rehabilitation rather than punishment is imperative. Unfortunately, the rationalization of punishing criminals runs deep in American society, which makes fighting for prisoners’ rights challenging.

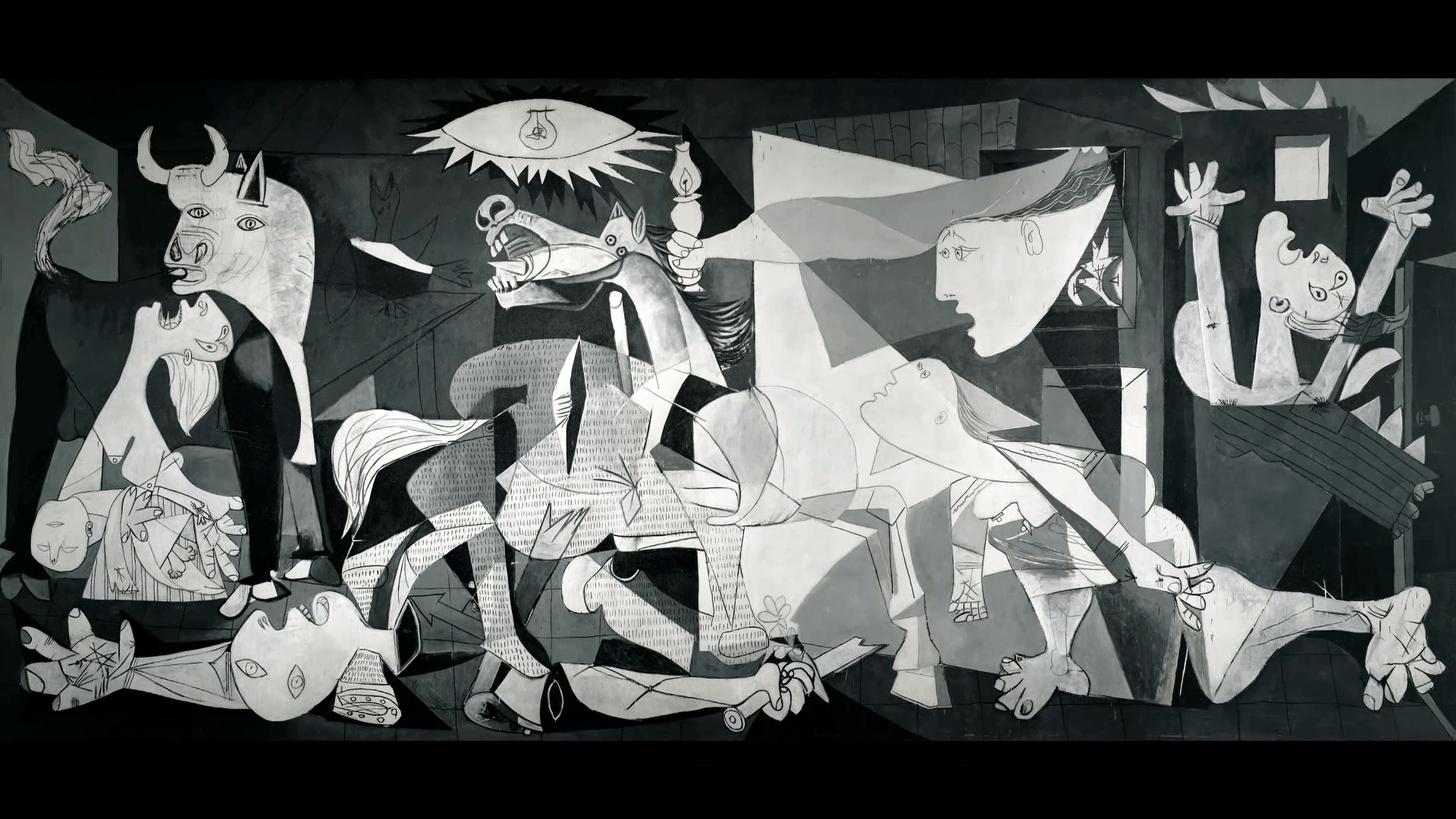

Picasso’s Plight

In the sky, there was a flash of light. Maybe it was God. Maybe it was the sun. No. No. It was a bomb. Screams pierced through the fire. Death everywhere. Help nowhere to be found.

Picasso likely heard personal accounts like the one above after on of the greatest tragedies of the Spanish Civil War—the Bombing of Guernica. Thirty-five days after the bombing, Picasso presented the world an anti-war message no one could ignore. Picasso had completed one of the greatest masterpieces of the 20th century—Guernica—a monumental black-and-white canvas spanning 25 feet by 11 feet, depicting the horrors of war. Shortly after completing the painting, a German officer entered Picasso’s apartment and asked Picasso, “Did you do that?” Picasso responded, “No, you did.”

So much suffering is all I could think when I first saw this painting. On the far left of the composition lies a woman wailing while clutching her dead child. Under the woman lies a dismembered arm, presumably belonging to the man whose head is detached from his body. He seems to be holding a broken sword. On the far right, a woman screams with her arms outstretched as she fails to escape a burning building. The mother, the child, the young man, and every other figure in the composition are victims of inexplicable war crimes. My heart wrenches everytime I see these figures. There is something innocent about the people scattered across the canvas. The child’s innocence is obvious, and for the others, they’re just civilians. Civilians who may have lived sinful lives, but civilians nonetheless. I see the dying baby and think what that baby’s life could have been. I think of the young man and think about what his life could have been. Every dying character evokes so much sorrow due to their apparent innocence and the fact that their lives were cut heartbreakingly short because of the war.

Dante’s Damnation

While reading Dante’s Inferno, I did not have this same visceral reaction when presented with the suffering of the sinners in Dante’s formulation of Hell. Of course, I felt pity and sadness toward the characters subjected to torture, but these negative emotions were not even close in magnitude to the negative emotions I experience when seeing Guernica. Dante himself also seems to experience subdued emotions when interacting with the inhabitants of Hell, especially as he travels deeper into Hell. Dante goes so far as to claim that some sinners deserve even more punishment than the punishment they are already experiencing. For example, when Dante sees Filippo Argenti in the River Styx, Dante says, “I am very eager to see that spirit soused within this broth… Soon after… I saw the [other] muddy sinners so dismember him that even now I praise and thank God for it.” In these lines, Dante wishes for Argenti to suffer even more, and his wish is granted when Argenti is torn to pieces by the other sinners in the River Styx.

Curiously, when I read these lines the first time, I was slightly disgusted by the idea of dismembering someone, but I didn’t feel much sympathy for Argenti. I was able to convince myself, similar to Dante, that Argenti deserves his fate. I was able to rationalize to myself that it is okay for someone to suffer so horribly. However, when presented with the dismembered young man in Guernica, I had a wildly different reaction. I felt a deep, visceral pain for the young man. My completely different reactions to the two characters being dismembered was unsettling to me. Why do I feel this way? Who am I to determine who deserves punishing? Do bad people deserve to be punished?

Philosophy of Punishment: Two Approaches

When considering punishment, we must talk about the most obvious structured punishment system in the United States—the American prison system. American prisons primarily serve two purposes: punishment and incapacitation (removing criminals from society via incarceration, house arrest, etc.). Our legal system is designed such that the punishment for a crime is commensurate to the severity of the crime and the culpability of the defendant. For example, if one steals a donut from Dunkin Donuts, the punishment would be a fine of no more than a couple hundred dollars. However, if one were to commit first degree murder—that is, premeditated murder—the punishment can be as severe as the death penalty. The idea of punishing criminals has been around for millennia. There is immense historical precedence, so it is oftentimes difficult to critically analyze whether or not punishing criminals is a practice we should continue to support. Punishing criminals is so pervasive in American society that it bleeds into my own reading of Dante’s Inferno. Even when reading horrific acts of torture, I still rationalize to myself that this kind of punishment is necessary. I tell myself, although punishing criminals is not ideal, it is necessary.

We have all been conditioned from the day we were born that criminals deserve to be punished. We were told that criminals must be held accountable for their heinous actions. Because if they aren’t held accountable, society will collapse. We were told that our safety would be in jeopardy. We were told that the streets would become more dangerous. That crime would rise. And that no one would be safe. However, we don’t need to think like this anymore. Punishing criminals is not a necessary evil. Punishing criminals is largely unnecessary, and we must make radical changes now to develop humane prisons.

Humane prisons change the way we think about imprisonment. Let’s revisit the two main purposes of American prisons. American prisons serve to punish criminals and remove criminals from society. Removing criminals from society is in fact necessary to maintain social fabric. There needs to be systems in place that remove murderers, child molesters, and other severe criminal offenders from society. Frankly, it is not safe to have this class of prisoners fully integrated into society. This is unfortunately the harsh reality. We have to remove them from society, which is a punishment in and of itself. However, we don’t need to introduce any extra punishments for criminals, which is what humane prisons aim to accomplish.

A prime example of a humane prison is Norway’s Halden Prison. Halden prison houses roughly 250 of the most “dangerous” criminals, including murderers, rapist, and pedophiles. The prison has no barbed wires, electric fences, towers, or snipers. There are no surveillance cameras in cells, hallways, or common rooms. The guards are unarmed so as to encourage a healthy relationship between the guards and the inmates. Almost no violence occurs within the prison. The main goal of the prison is rehabilitation—not punishment. The prison is staffed by teachers, healthcare workers, and social workers. These staffers serve to build community within the prison as well as rehabilitate the inmates, so they can be reintegrated into society.

This prison doesn’t even sound like a prison; it seems more like a hotel! Some people doubt the efficacy of humane prisons. They claim that by not punishing criminals, there is no reason for people not to commit crimes. They argue that punishment is a deterrent for crime. However, these claims are demonstrably false. Daniel S. Nagin discusses deterrence in his essay, “Deterrence in the Twenty-First Century.” Nagin concludes that “[t]he evidence in support of the deterrent effect of the certainty of punishment is far more consistent than that for the severity of punishment.” In other words, the actual punishment is not an important factor in deterrence; rather, the certainty of being caught is the most important factor in deterrence. Nagin further states, “[t]here is little evidence that increasing already long prison sentences has a material deterrence effect.” Thus, it appears that if we want to reduce the frequency of crime, we shouldn’t punish criminals severely. We should instead focus on convincing the public that if they commit a crime, they will almost certainly be caught by the police.

Nagin proposes an effective incarceration system, but the current American prison system is far from his vision. Nearly all American prisons are overcrowded. Sanitary conditions within these prisons are horrendous, resulting in diseases running rampant. Prison conditions were especially inadequate during the COVID-19 pandemic. “A majority of the largest, single-site outbreaks since the beginning of the pandemic have been in jails and prisons,” according to the COVID Prison Project. Besides unsanitary conditions, prisoners also must face horrific treatment from the very people who are supposed to be protecting them—prison guards. American “prison officials are not trained mental health providers, and their methods frequently do more harm than good to these populations and the prison population as a whole. Incarcerated individuals often endure physical and psychological abuse, neglect and humiliation at the hands of prison guards,” according to the Fair Fight Initiative. I could go on about the failures of the American prison system, but the bottom line is clear. American prisons do not serve to rehabilitate. They serve to punish. They serve to make prisoners’ lives living hells. Prisoners are dehumanized to the point where people do not even extend human rights to prisoners. By subjecting prisoners to such cruelty, we are essentially ripping away their humanity. And when we begin to rip away their humanity, we begin to rationalize that prisoners do not deserve human rights.

Let’s explore the difference in outcomes of prisoners who experienced the harsh prison system of America versus the outcomes of prisoners who experienced the humane prison system of Norway. One good way to measure the success of a prison is to look at recidivism. Recidivism is the tendency of a convicted criminal to relapse into criminal behavior by committing another crime. The recidivism rate of Norway is 20%, while the recidivism rate of the U.S. is a whopping 76.6%. In other words, A prisoner in Norway is 4 times more likely to be rehabilitated than a prisoner in America. This enormous difference highlights how successful Norwegian prisons are and how unsuccessful American prisons are. These data show that Norway’s prisons actually do rehabilitate prisoners and reintegrate prisoners into society. American prisons, on the other hand, are failing miserably. Clearly, the American style of harshly punishing prisoners is not effective in rehabilitation. After leaving U.S. prisons, prisoners are highly likely to commit another crime. This is a lose-lose situation for everybody. The everyday citizen is harmed by crime, and the criminal hurts themselves by committing the crime. By committing yet another crime, they are sentencing themselves to even more punishment.

Furthermore, even if freed American prisoners do not recidivate, they still suffer significantly. Although they do not go back into the torturous prison system, they fail to integrate back into society. Freed prisoners have little to no mental health support. Mental health support is absolutely necessary given that the vast majority of American prisoners are subjected to severe trauma. A study in 2014 found that “[r]ates of current PTSD symptoms and lifetime PTSD were significantly higher (30 to 60 %) than rates found in the general male populations (3 to 6 %).” Another study found that “[s]uicide risk was 62% higher among previously incarcerated individuals compared with the general population.” These data show that the punishment for prisoners does not end after they are freed. The cruel conditions of prison scar prisoners for life, effectively sentencing them to a life of punishment. Ex-convicts’ lives are ruined because even after leaving prison, they struggle to reintegrate into society. Ex-convicts have low scores of wellbeing and sense of belonging. The support system for freed prisoners is decrepit. According to a 2021 study, roughly 60% of formerly incarcerated people are currently unemployed. If ex-convicts cannot even find jobs, how can we expect them to reintegrate successfully? Without a revenue stream, without a mental health support system, formerly incarcerated people are doomed. To quote Brain Stevenson, author of Just Mercy, “simply punishing the broken – walking away from them or hiding them from sight – only ensures that they remain broken and we do, too. There is no wholeness outside of our reciprocal humanity.” When we convict a person to prison for a certain number of years, we are not just sentencing them for those certain number of years; we are sentencing them to a life of punishment.

Conclusion

Ultimately, no one deserves punishment, and it seems like we don’t even need to punish prisoners for their crimes. In fact, punishing prisoners hurts everyone. It hurts the prisoner; it hurts the everyday citizen; it hurts society. We must shift our focus from retribution to rehabilitation. To make this shift, we must first change the way we think of punishment. If no one deserves punishment, then why did I react to Filippo Argenti’s torture in Dante’s Inferno? I would argue that my rationalization of Argenti’s punishment is indicative of a deeper, more ingrained attitude in American culture. The rationalization of punishing those who have committed crimes or sins runs deep in American culture.

We must change this kind of thinking and adopt radical empathy. Radical empathy is the idea of extending “empathy to everyone it should be extended to, even when it is unusual or seems strange to do so.” The reality is that it does seem unusual to extend empathy to prisoners. It is easy to typecast prisoners into some outgroup, but we must not fall into this factionalist mindset. We must realize that prisoners are humans too, but coming to this realization is not enough. We must actively persuade our friends and family that prisoners are human too. Humans who deserve human rights; humans who deserve more than a life of suffering; humans who deserve our empathy. We can create a safer, happier world by extending empathy to prisoners, but we must take action.

Prisoners do not have anyone to speak for them, so we must step in and advocate for them. Many prisoners lose their right to vote, so their voices are silenced in the realm of American politics. Most politicians ignore prisoners’ rights because prisoners cannot even vote for politicians. It is not in the interest of politicians to advocate for a bloc that cannot even vote for them. Thus, it is up to us to stand and fight. Vote for politicians who actually care about prisoners’ wellbeing. Encourage those who defend the rights of prisoners. Be a radical empathist.

Considering my reactions to Guernica and Inferno through the lens of radical empathy, I have realized that I should react to both depictions of punishment similarly. Just because Filippo Argenti may have lived a sinful life, does not mean he deserves to be punished. And it doesn’t mean that I should rationalize his punishment either. In the same way that I felt a visceral pain for the dismembered man in Guernica, I should try to feel that same empathy for Argenti. I am denying Argenti’s humanity by failing to empathize with him. My failure to empathize with Argenti extends directly to the way we think about the punishment of prisoners. By expanding our circle of compassion and empathy, we can develop a society where prisoners aren’t punished unnecessarily. Criminals are not monsters; they are victims. We must advocate for their rights because if we do not, no one else will. I’m hopeful though. I see a bright future: a future where when we hear the word “prison,” we won’t be thinking about punishment; rather, we’ll be thinking of rehabilitation.