Utilitarianism and the Experience Machine

Utilitarianism is the ethical theory that the goodness of an action is determined by the consequences of that action. In this post, I argue that hedonistic extreme utilitarianism is the strongest form of utilitarianism. Then, I rehash Robert Nozick’s Experience Machine thought experiment. Finally, I contend that Nozick misinterprets pleasure, which compromises his argument.

I do not identify as utilitarian. This post assumes moral realism.

Clarifying Utilitarianism

Hedonistic utilitarianism states that the goodness of an action is determined by how much pleasure the action generates or how much suffering it alleviates. The hedonistic utilitarian assigns terminal value to pleasure, where terminal values are values that are pursued for their own sake. All other values that have the tendency to generate pleasure are assigned instrumental value, where instrumental values are values that are pursued for the sake of realizing terminal values. For example, knowledge is an instrumental value. In general, gaining knowledge is good as it tends to generate pleasure, though the knowledge is not valuable for its own sake. Thus, we may argue that knowledge is a terminal value.

Impartiality is a key characteristic of hedonistic utilitarianism. Suppose there are two people, person A and B. Impartiality implies that the pleasure person A experiences is equally as valuable as the pleasure experienced by person B, assuming both experienced pleasures are commensurate. It does not matter when or where the pleasure is experienced. However, it could be argued that for certain individuals, their pleasure matters more only as a means to generating more total pleasure. Consider a historical figure who has generated/alleviated a significant amount of pleasure/suffering in the world: Edward Jenner, the inventor of the smallpox vaccine. It could be argued that Jenner’s well-being is more important than others if increasing his well-being increases his output. Jenner’s invention has saved over a 100 million lives. In this case, we can treat Jenner’s well-being as instrumental in achieving the terminal goal of alleviating suffering in aggregate.

Hedonistic utilitarianism (I will use just utilitarianism to refer to hedonistic utilitarianism moving forward) applies to every single action we take. This means that we ought to “test individual actions by their consequences” (Smart 344). This is not to say that we should work through the utilitarian calculus for every decision we make. For if we were to engage in such calculus for every action, we would fail to act in timely circumstances and thus fail to actually act in ways that would increase pleasure. Many times we are forced to make split-second decisions and in these cases, we should rely on common sense morality as common sense morality usually results in the same action that a utilitarian would have committed if they had done the calculations. Thus, it seems useful to try to formalize this common sense morality into a set of rules that we can follow in our day to day lives. When we derive such a set of rules, we evaluate the strength of a rule by its tendency to generate pleasure or reduce suffering. Thus, it could be argued that a rule such as keeping promises is a good rule as it generates pleasure on average. It is important to note that these rules are just rules of thumb; the rules have no force in themselves. If disobeying the rule results in more pleasure, then one ought to disobey the rule. This is the view of the extreme utilitarian. The restricted utilitarian would argue that one ought to obey the rule always regardless of the outcome. To demonstrate the irrationality of restricted utilitarianism, consider the following case.

Suppose that there is a rule R that results in the maximum pleasure and minimum suffering 99% of the time. Let’s say that you are in a situation where you have completed the utilitarian calculus and determined, with 100% accuracy, that disobeying R would result in a superior outcome (more pleasure and less suffering) than if we were to obey R. What should we do? The restrictive utilitarian would argue that we ought to obey R and settle for the suboptimal consequence even though we know that the consequence is categorically worse than if we disobeyed R. The extreme utilitarian would disobey R and proceed with the action that generates more pleasure. In this situation, it is irrational to knowingly choose an action that results in a suboptimal outcome. To knowingly opt for an outcome with less pleasure, is to reject the notion that the consequence is what matters and thus restrictive utilitarianism may not even be a coherent form of utilitarianism.

Extreme utilitarianism may initially seem like an uncomfortable ethical system. One may argue, ‘how could you ever trust a utilitarian if they are so willing to reject integrity given the circumstances.’ Upon further inspection, the extreme utilitarian would almost always act with integrity because if an extreme utilitarian were not to be trusted then they would severely limit their ability to maximize pleasure. Thus, the extreme utilitarian would take honesty very seriously and behave similarly to a Kantian. The cases where the extreme utilitarianism would differ from the Kantian are cases where it’s obvious to lie (e.g. lying to a Nazi officer that you aren’t hiding Jewish refugees). In edge cases where common sense morality does not give an obvious answer to whether one should lie or not, the extreme utilitarian would “ascribe decisive importance…[to the] weakening of faith in the institution of promising” (Smart 344). Thus, we have shown that extreme utilitarianism is surprisingly congruent with common sense morality.

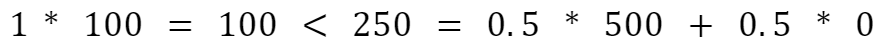

Naturally, when discussing utilitarianism, the notion of condemnation and praise arises. For any action X, should we condemn or praise X? Suppose there is a drowning man, and a passerby jumps in and saves the drowning man. Assuming there was no time to deliberate, it is clear that the extreme utilitarian would praise the passerby. If instead the drowning man was Hitler and the passerby did not know this information, should the action be condemned or praised? An extreme utilitarian who knew that the drowning man was Hitler would still praise the passerby for saving Hitler. It is important to note that the extreme utilitarian can praise someone for committing a wrong action. In this example, praising the passerby reinforces the fact that saving drowning people exists within “a class of actions which are generally right” (Smart 347). In cases of high uncertainty or minimal information, we judge one’s actions not by their consequence but by the action’s expected value and the action’s alignment with rules (i.e. whether the action obeyed a set of rules that generate pleasure on average). Expected value is crucial to determining whether an action is praiseworthy. Suppose there are 500 people in a burning building, and you have two options: a) 100% chance to save 100 lives and b) 50% chance to save everyone but a 50% chance to save no one. Let’s say you choose option b) and you unfortunately save no one. The extreme utilitarian would praise you for choosing option b) because option b) has higher expected value than option a),

The formulation of utilitarianism I have laid out thus far is hedonistic extreme utilitarianism. Robert Nozick disagrees with this version of utilitarianism. He rejects the notion that pleasure and happiness are the only terminal values. He argues that humans care about things in addition to our experiences—that is, we should not exclusively assign terminal value to pleasure and that humans are more than just experiencers of our environments. To support his belief that humans care about more than just pleasure, Nozick devises the Experience Machine thought experiment.

Nozick’s Experience Machine

“Suppose there were an experience machine that would give you any experience that you desired” (Nozick). This experience machine would be so realistic that it would be impossible to differentiate between reality and the experience machine. Ignore issues like whether your loved ones would experience pain knowing that you’re no longer in their lives. In the experience machine, you can experience the greatest of all joys and choose whatever experience you could possibly wish for. Would you plug in? Nozick argues that most people would not want to plug in. He argues that people would not plug in because there are things that matter to us “other than how our lives feel from the inside” (Nozick). Nozick proposes a few things that might matter to us.

First, we want to actively do things. We don’t just want to experience things or have things done to us. We desire to actually change our environment around and bring about real change. Second, we want to be in control of our life and experience reality. We don’t feel satisfied in a “man-made reality” (Nozick). We want to live our lives “in contact with reality (Nozick). One way to illustrate our desire to be in contact with reality is to imagine the following description: a person’s “apparently faithful mate carries on secret love affairs; their apparently loving children really dest them; and so on” (Nozick). Nozick claims that no one would claim that such a life is an excellent life. He highlights that the perceived faithfulness of one’s partner is not enough. The truth value of the partner’s faithfulness is what really matters. Thus, humans fundamentally do value truth and the knowledge that our experiences are rooted in reality.

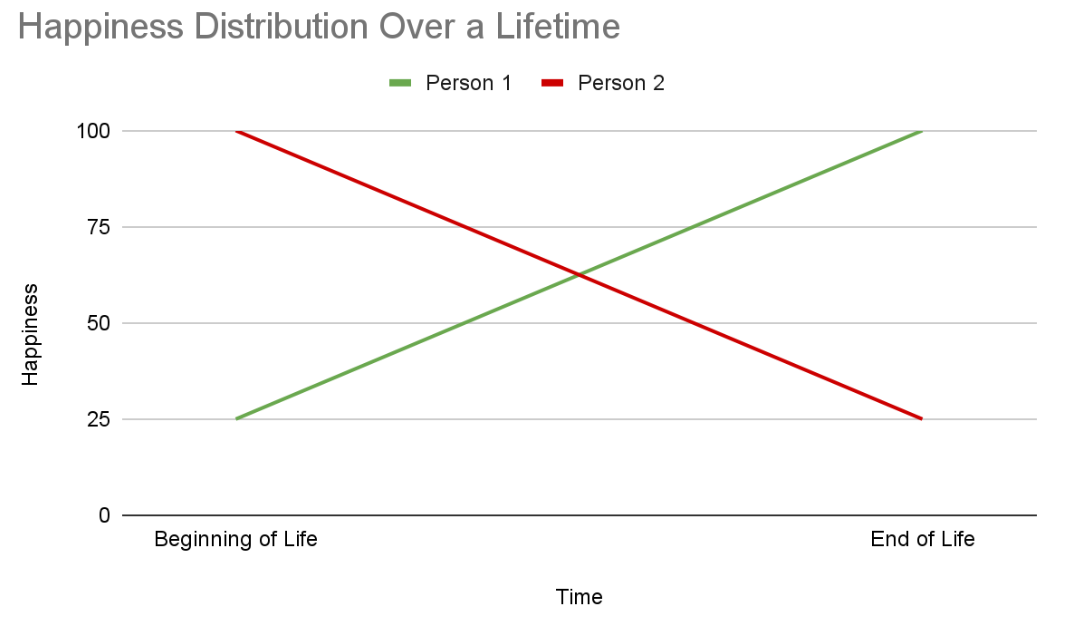

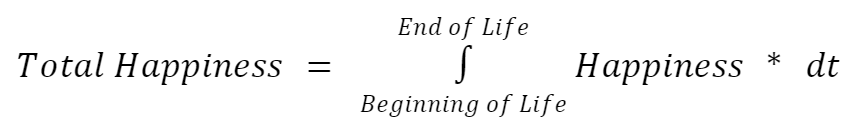

Nozick proceeds to tear down hedonism by highlighting that in addition to experienced happiness, we care about how that happiness is distributed across our life. Imagine the following graph with happiness on the vertical axis. time on the horizontal axis. Total lifetime happiness is the integral from beginning of life to end of life with respect to time (i.e. total lifetime happiness = area under the curve).

Nozick argues that although the total happiness of person 1 and 2 are equal, most people would prefer person 1’s life. He claims that “we would prefer a life of increasing happiness to one of decrease” (Nozick). In fact, in some cases, we may even prefer lives with less total happiness “in order to gain a more desirable narrative direction”—that is, regardless of the integral (total happiness), we may prefer the life with a positive derivative (positive slope) than a life with a smaller or negative derivative.

Nozick’s Mistake

Nozick appears to make a powerful argument against hedonism, but his argument hinges on a flawed definition of pleasure. He only considers sensory pleasures in his account for pleasure, but as we will see in the following section, there exists pleasures other than just sensory pleasures.

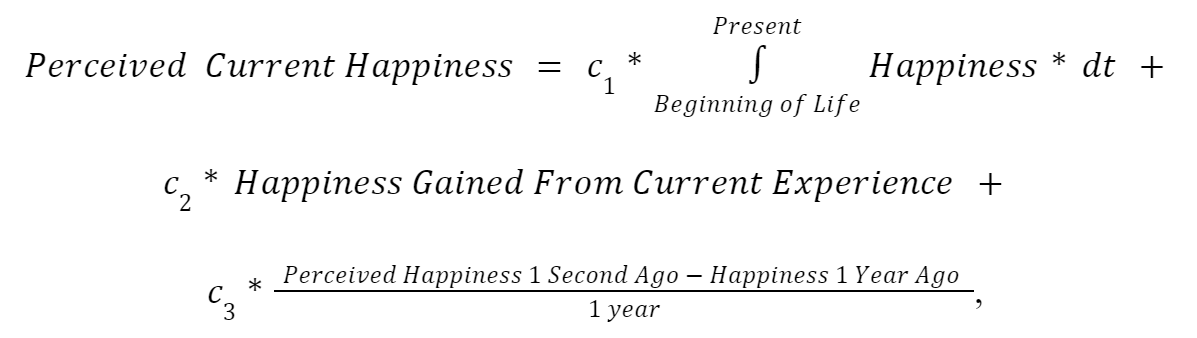

I will begin by responding to Nozick’s claim that we care about how our happiness is distributed across our lifetimes. Nozick thinks that we care about the “narrative direction” of our lifetime happiness for its own sake (Nozick). Here, Nozick is failing to consider that our preference for narrative direction is an example of a metapleasure. We care about the narrative direction because it directly affects our perceived happiness. We derive pleasure from knowing that our lifetime happiness is on the rise. Thus, we have illustrated that narrative direction is instrumentally valuable in achieving what we really care about—happiness. When we take into account metapleasures that affect our perceived current happiness, we may arrive at a more complex but more accurate equation of happiness

where the first term corresponds to satisfaction or fulfillment (i.e. how pleasurable/happy has my life been thus far), the second term corresponds to the happiness gained from committing an action in the present moment, and the third term corresponds to the distribution of happiness over the past year (i.e. the slope of my happiness over the past year). For the slope calculation, I consider only the past year because this timescale seems more in tune with our intuitive metapleasure as compared to timescales of our entire life so far or instantaneous timescale (derivative).

Nozick further misinterprets pleasure by ignoring metadesires. I will define metadesire as the desire that our desires are truly satisfied. We derive pleasure from knowing that we fulfill our desires “in contact with reality” (Nozick). Metadesire is not some separate thing we care about that has intrinsic value; instead, it is just another form of pleasure. When Nozick claims that “we desire… to live (an active verb) ourselves, in contact with reality,” he is actually identifying a metadesire, which is completely compatible with hedonism. Applying this model of metadesires to Nozick’s example of “an apparently faithful mate [who] carries on secret love affairs” (Nozick), we realize that we desire that our faithful mate is actually faithful to us and derive pleasure from such a belief that our mate is actually faithful. Nozick thinks that such a metadesire is a value distinct from pleasure, but this is a narrow and naive view of pleasure. The crux of his misunderstanding is that he conflates pleasure with sensory pleasure. He fails to recognize that there are other pleasures besides sensory pleasure.

Thus, when we consider all forms of pleasure (sensory pleasures, metapleasures, and metadesires), it is unclear whether we would actually plug into the experience machine. We may argue that the experience machine would fail to satisfy our metadesires, and thus it is not worth plugging in. The fulfillment of our metadesires may play enough of a role in the hedonistic calculus to suggest that we opt for a life of fewer sensory pleasures “in contact with reality” over a life with more sensory pleasures in the experience machine.

In my opinion, the hedonistic utilitarian’s refutation to Nozick is compelling. Nozick’s criticism falls apart due to his conflation of pleasure with sensory pleasure. His failure to recognize metadesires and metapleasures makes hedonistic extreme utilitarianism coherent with the decision to reject the experience machine. Thus, hedonistic extreme utilitarianism still holds.

References

Smart, J. J. C. “Extreme and Restricted Utilitarianism.” The Philosophical Quarterly (1950-), vol. 6, no. 25, 1956, pp. 344–54. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2216786. Accessed 17 Nov. 2022.

Nozick, R. “The Experience Machine.” 1974, 1989, pp. 1-6. Accessed 17 Nov. 2022.